Transcribed by Philip Crompton

The Lions

The hot African sun was shining on the calm waters of a narrow river, which flowed slowly through a dark jungle. In this jungle lived a family of lions – a huge lion, a fierce lioness, and seven little cubs. They had lived a very quiet life, and now lay basking quietly in the sun, while the cubs rolled in the grass or played around their mother. Suddenly the lion sprang up and gave a low growl, and pricked up his small ears, for coming down the river was a small boat, in which were four hunters, their guns ready. The lioness raised herself quickly, and, seeing the danger, carried her cubs off into the darkest depths of the jungle, and then bounded back to the side of her mate. And there together the noble beasts awaited the coming danger. Before long there came a flash of fire, and the lioness uttered a low moan, and fell to the ground. In a minute she was up again, but with a deep wound in her shoulder. Again a shot broke the stillness of the jungle, and this time the lion fell without a sound. They did not understand this sort of fighting. The lioness in great distress ran round her fallen lord. Then she ran to the bank, and sprang on the nearing boat. A shot went through her head, and with a thud she fell into the boat, half sinking it. The hunters rowed away, leaving the lion on the shore. As he lay dying on the banks of the river he thought, “I have never hurt any man; why should they kill my mate and leave me dying? If a deer or any animal on whom I feed had killed my mate and wounded me, it would have been fairly done; but one whom I have never hurt, it is not.” That night when the moon came out it shone on the noble lion lying dead; and the little cubs, having found their way back, were licking his wounds gently, wondering why their father did not wake, and thinking their mother would soon return. But he never woke again, and the lioness, who was no use to the hunters, was lying in the bed of the deep stream. All that night the poor little cubs yelped and ran about. Many days of hunger followed. One day the hunters returned, and captured two of the family, who are now caged up with nothing of the glorious jungle near, but a faint memory, and a strong instinct to burst the cage and wander off to the wilds again.

By Dorothy Stirrup – Hawthorne, Dukes Brow, Blackburn

Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, 25th November 1905

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

The Scarlet Chrysanthemum

In the middle of a large conservatory stood a tall white chrysanthemum surrounded by small ones of a similar kind. At the very end of the flower house, in a dark corner, leaning sadly against the glass, was a little scarlet chrysanthemum. Once she had been happy, even in this dark corner, for another yellow chrysanthemum had stood by her, and they lived happily together far from the queen of the conservatory, the white chrysanthemum. But that morning the yellow flower had been put in the group surrounding the beautiful queen and had forgotten all about her friend. The little scarlet flower looked wistfully across at the pretty group, but they turned their heads away proudly. The next day she was put among them, but they would not look at her, she was so much smaller than they. But the beautiful queen saw her, and bent graciously down and said, “I have often seen you in that corner over there, and I am very glad you have been put here. Don’t mind if the other flowers scorn you; I will love you always.” The little chrysanthemum murmured softly, “oh, dear queen, how kind you are to me.” She lived happily day after day, growing rapidly tall and beautiful. One day a careless gardener left the conservatory door open, and the bitter frost entered, biting the flowers’ slender petals and leaves. Quickly the scarlet chrysanthemum spread her broad leaves before the delicate queen, and all night sheltered her from the piercing cold. At last the door was shut, and a gardener came to examine the poor flowers. Many were seriously damaged. The queen had only one or two blighted leaves; but the poor scarlet flower had many injuries, and many leaves and petals were taken off. Then she was put back in her old place, but by and by she was brought out again, and placed, not on a level with the other flowers, but higher even than the queen. And the scarlet flower and the white one reigned happily together over all the smaller chrysanthemums.

By Dorothy Stirrup, Hawthorne, Dukes Brow, Blackburn

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, 9th December 1905

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

In Fire-Land

Through The Meadow Gate

The Roses and the Moonbeam

In The Land of the Water Lilies

The Adventures of Billie Blue-Bottle

In Fire-Land

The fire was very low and red, and Marjorie was watching the queer shapes lighten and darken. There were hills and valleys, caves and rocks, and even little houses, with trees and flowers growing round them. Marjorie had been sitting there for such a long time, until she fancied she saw little people running about in a great hurry. At last they gathered round a little man who stood on a rock above the others. He seemed to be speaking very excitedly about something. Marjorie leant forward to hear him, until her face nearly touched the bars. But the fire did not seem to burn at all. And this is what she heard: “Her Majesty the Queen of Fire-Land is giving a picnic in the castle grounds, to which all are invited, and ____” He stopped suddenly, for he had caught sight of Marjorie’s face. He screamed and jumped from the rock, and ran to a large castle near. The people immediately followed, and Marjorie saw their frightened faces peeping out of the castle windows.

The fire was very low and red, and Marjorie was watching the queer shapes lighten and darken. There were hills and valleys, caves and rocks, and even little houses, with trees and flowers growing round them. Marjorie had been sitting there for such a long time, until she fancied she saw little people running about in a great hurry. At last they gathered round a little man who stood on a rock above the others. He seemed to be speaking very excitedly about something. Marjorie leant forward to hear him, until her face nearly touched the bars. But the fire did not seem to burn at all. And this is what she heard: “Her Majesty the Queen of Fire-Land is giving a picnic in the castle grounds, to which all are invited, and ____” He stopped suddenly, for he had caught sight of Marjorie’s face. He screamed and jumped from the rock, and ran to a large castle near. The people immediately followed, and Marjorie saw their frightened faces peeping out of the castle windows.

Soon, however the door opened, and a pretty little fire lady walked down the steps. She wore a crown and royal robes. She came quite close to Marjorie, and then said, “Why will you frighten my people so, and just when we were going to enjoy ourselves?” “Oh, please your Majesty I did not mean to be rude; but may I come into your beautiful Fire-Land?” Marjorie asked. When she said this the people shouted. “No, no!” but a little old man came up and asked the Queen to grant her request. At last she consented, and touched Marjorie lightly on her shoulder. Marjorie felt herself growing less and less until she was small enough to creep through the large bars but she was much bigger than the others. The fire was not at all hot, and she walked up to the castle to the Queen.

Soon a bell rang, and everyone went to the farthest end of the castle grounds. There they danced and played games, and the Queen joined in. Afterwards, they had tea, but Marjorie could not eat anything, because the food was cinders. Suddenly a funny little man ran up, very much out of breath. “Oh, your Highness, a great giant is going to put great clumps of coal on our land, and we shall be killed!” he cried. Everybody rushed hither and thither in great confusion. At last Marjorie thought of something. Her handkerchief remained the same size as before, and, gathering all the people she could get hold of, she wrapped them up in it. Then she stepped out, grew to her ordinary size, and pulled the handkerchief out of the fire. “The giant,” was only Jane, the housemaid putting coal on the fire, and she was very much surprised to find Marjorie holding a handkerchief full of cinders. Marjorie tried to explain, but Jane only laughed at her.

By Dorothy Stirrup Duke’s Brow, Blackburn

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, 27th January 1906

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

back to top

Through the Meadow-Gate

Mary stood looking through the big white gate on to the long green grass, covered with cowslips, beyond. “How I wish I could get through, but I never can open this big gate,” she sighed, “Cowslips, pretty cowslips, let me in, do.” But still the pretty yellow flowers went on nodding their heavy heads gently. The little girl laid her curly head on the white bars, and watched them bend and quiver in the warm summer wind. For a long time she watched them, until they seemed to move slowly as if to silent music.

Mary stood looking through the big white gate on to the long green grass, covered with cowslips, beyond. “How I wish I could get through, but I never can open this big gate,” she sighed, “Cowslips, pretty cowslips, let me in, do.” But still the pretty yellow flowers went on nodding their heavy heads gently. The little girl laid her curly head on the white bars, and watched them bend and quiver in the warm summer wind. For a long time she watched them, until they seemed to move slowly as if to silent music.

At last she heard the little bells chime. The cowslips swayed gently to and fro, and parted in the middle, forming a wide path down the meadow. Mary looked eagerly up it, but she could see nothing. “What is the matter?” she asked a cowslip standing near. Oh! the Flower Lady is coming! Hurrah! Hurrah!” and she shook her seven bells gaily, making merry music. Then Mary saw tiny golden horses galloping down the path, with sweet cowslip fairies on their backs, but no Flower Lady was to be seen. The horses stood in rows down the path. Soon some golden carriages came down, drawn by golden horses. In them were fairies, ladies-in-waiting to the Flower Lady.

Many more lovely fairies came, but it was a long time before the Lady came. At last, amidst loud cheers and fairy music, a lovely lady did make her appearance. She was dressed completely in cowslip silk, and her golden hair was crowned with the tiny flowers. She stepped daintily out of her carriage and called the cowslips to her. “My people,” she said in a silvery voice, “I have come back at last: the Goblin King has released me from my prison, and we will dance and be merry once again.” The cowslips danced and sang merrily, and Mary watched them eagerly. By-and-by the Lady stopped them. “Now we will play hide-and-seek,” she said, and at once the flowers ran helter-skelter through the long grass.

Suddenly a fearful noise floated over the meadow. “Moo-o, Moo-o,” and again “Moo-Moo-o-o-o,” and crashing through the hedge came Dolly, the big black cow. Instantly the flowers stood still, but Mary saw them shaking with fear. “Poor, dear flowers,” she said. “Shoo-Shoo! Bhoo!” she screamed at Dolly, and the terrified cow kicked up her heals and cleared the hedge with a bound. Soon after the Flower Lady ran up to Mary. “Oh, you good little girl!” she said gratefully. “It was so kind of you. Can I do anything for you now?”

“Give me permission to come into this lovely field, lovely lady.”

“Certainly,” she answered, but ran away quickly, for Dolly’s obstinate tail appeared above the hedge top. Ever after the gate has opened easily to the little girl, but Mary will not let the terrifying cow go near to the Lady’s little cowslips.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday 14th April1906

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

back to top

The Roses and the Moonbeam

A pretty little cottage stood in a country lane, all alone. It was covered with the most beautiful red roses, which crept even over the thatched roof. In this cottage lived a little girl with her grandmother. Every evening when she went to bed she leaned out of her window to say good-night to the roses. One night she could not go to sleep, and she watched the moon shine on the nodding flowers. Marjorie (for that was her name) jumped out of her little bed and went to the open window. She looked out on to the moon-lit lane. Something seemed to be moving on the ground, and now and then she saw a bright gleam.

“What can it be?" she said wonderingly.

“Come and see," said a little voice in her ear, and turning round she saw a tiny fairy.

“Oh! oh!" gasped the astonished little girl, “Who are you, please?"

“I am only a little rose fairy, but I have watched you every day, and think you deserve to come to ____"

At this moment a whistle blew, and taking Marjorie's hand she said, “Step out on to the rose leaves, and don't be frightened." Marjorie did so, and immediately the flowers fluttered to the ground. Then the fairy stepped off the leaves, and the little girl followed. To her great surprise she saw coming down the lane a troop of dancing fairies. They stopped before here, and bowed low. “Welcome!" they said together.

The fairy who had brought her from her room asked her if she would dance with them. Of course, she said “Yes," and at once began to trip lightly with the other fairies down the lane. As she danced, she became smaller and smaller, until she was exactly fairy size. On, on the danced, singing as they went over hills, down valleys, until they reached a little green gate. It was opened at once, and Marjorie and the little people ran into a lovely rose garden. Trees and trees of red roses grew there. Each fairy jumped into a rose and played among them, covering themselves with yellow dust and eating honey. Marjorie did the same and enjoyed herself playing hide and seek among the petals of an enormous rose with three other little fairies. They all sat down on the leaves and ate honey out of the nearest flowers.

All this time the moon had been shining, and her straight silvery beams shone right into the rose in which Marjorie sat. The beam looked so firm and broad Marjorie put out her foot and touched it; it was quite hard. Then she stepped on to it, and walked slowly, a little way up the beam. Then she called to the other fairies, who crowded up the beams, right to the moon's smiling face at the top. All the fairies came down again, but poor little Marjorie, not being a real fairy, was very tired when she got to the top.

“Oh, Moon, I am tired," she sighed.

“Never mind," said the moon's voice kindly, “slide down on this."

Instantly a little sledge appeared on the beam. After thanking the moon the little girl got in, and away she went down the silvery streak. She got of at the rose garden, where the fairies were looking for her, and they were so glad to see her again. But as the day was beginning to dawn a fairy blew a whistle, and soon Marjorie heard “Buzz, buzz," and a big bee flew into the garden. “Carry her to her own room," said the fairy as she put Marjorie on his back, and away he flew, and the little girl resting in this velvety coat fell asleep. When she woke there, she was in her own pretty room, with the roses peeping in at her window.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday 14th July, 1906

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

In The Land of the Water Lilies

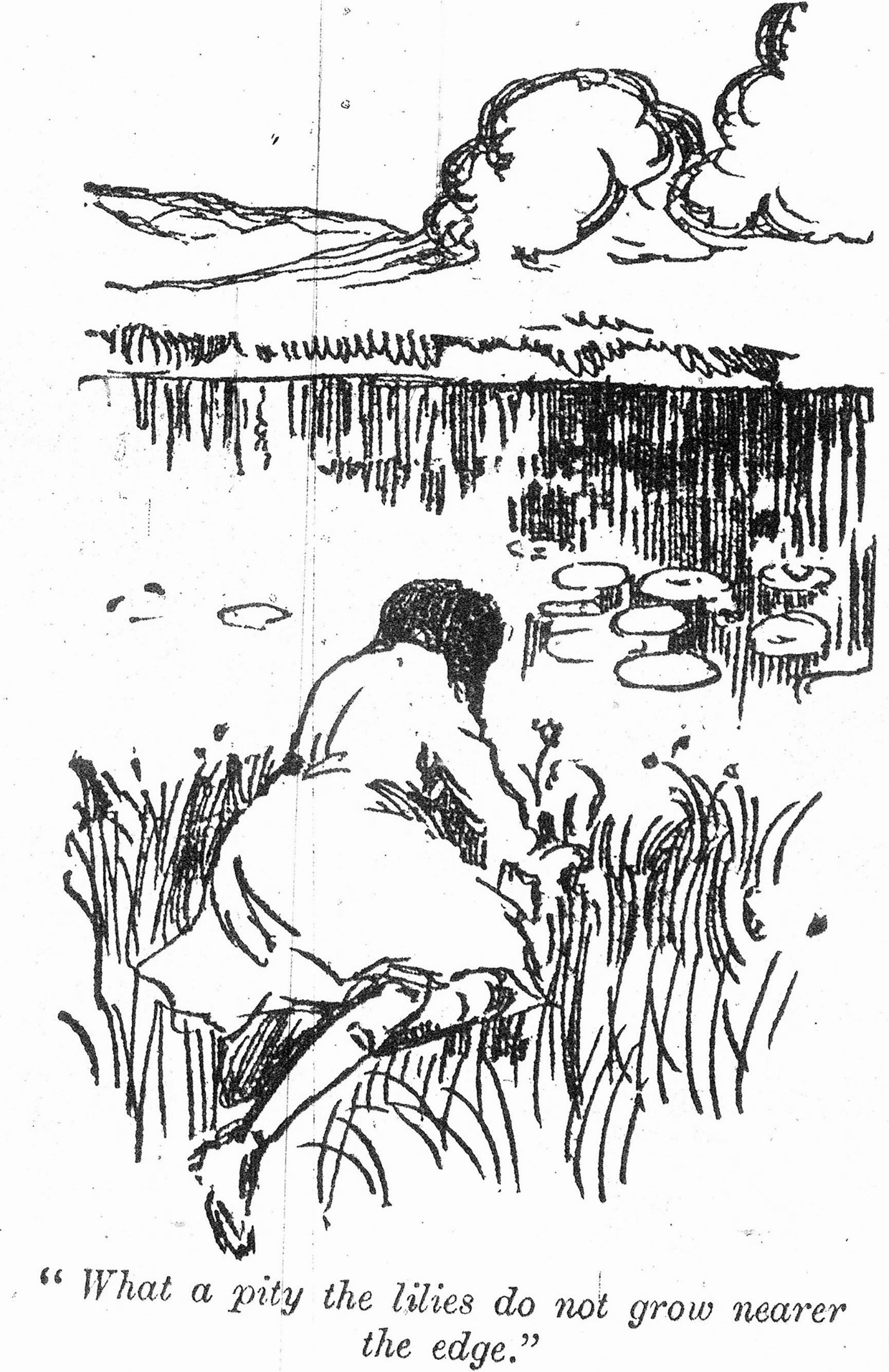

Mabel was lying on the banks of a wide river, looking at the pale-gold water lilies floating about among the broad green leaves and clear water. “What a pity those water lilies don’t grow near the edge,” she said. I’d get heaps and heaps and put them in a bowl, and take them to mother, and oh! wouldn’t she be pleased.” She lay there gazing at the fishes swimming about amongst the stones, until the peacefulness of everything and the warm sun made her sleepy, and soon she shut her eyes and dreamily thought how nice the water lilies would look on her mother’s table.

Mabel was lying on the banks of a wide river, looking at the pale-gold water lilies floating about among the broad green leaves and clear water. “What a pity those water lilies don’t grow near the edge,” she said. I’d get heaps and heaps and put them in a bowl, and take them to mother, and oh! wouldn’t she be pleased.” She lay there gazing at the fishes swimming about amongst the stones, until the peacefulness of everything and the warm sun made her sleepy, and soon she shut her eyes and dreamily thought how nice the water lilies would look on her mother’s table.

Lazily opening her eyes, she was astonished to see hundreds of golden flowers coming swiftly down the river. Mabel sat up quickly, rubbed her eyes, shook her curly head, and stared at the approaching flowers. She thought she heard a slight whistle, different from that of a bird, come from among the lilies. “How queer it is that they should come sailing down the river like this; perhaps I shall be able to get some now, for they are sure to stop by that big stone, till they reached the big stone.” On, on the flowers came till they reached the big stone in the middle of the river, and then stopped.

“I won’t pick them now,” she said, half aloud. “Then they won’t die.” She shut her eyes again, wondering at the sudden appearance of the flower. Soon she was fast asleep with her golden curls tumbled over her rosy little face. The moment she was asleep there was a stir among the flowers in the river, and out of every flower popped a little fairy with a golden and green dress on, and all gazed anxiously at the little sleeping figure on the green earth. “Is it safe?” one fairy asked of the other nearest to the bank. “Yes, I think so now,” was the answer. “I was so frightened she would see us, but I don’t think she has done.”

“Oh dear, what shall we do?” cried a little fairy in dismay. “We can’t get on, because this enormous stone is stopping up the way, and if that little mortal on the bank wakes up she will certainly get hold of us.”

“Oh, what shall we do?” they asked hopelessly of one another. “Oh, I know,” suddenly said one fairy. “We will wait till that little girl wakes up and ask her to move it for us. Do you all agree? We can ask her not to touch us, you know,” she added. “Oh yes, yes; what a good idea, “they cried, and sat down in their flowers to wait for Mabel waking.

Soon the little girl stirred, tossed her hand into the water, and woke with a start. She sat up and looked round her and saw the band of water lilies in the river. She got up and stepped on to a stone at the side of the river, and bent down to get a lily, when something moved among the golden petals, and a tiny fairy stepped out on to a green leaf. Mabel rubbed her eyes to see she were dreaming, but no, there really was a fairy standing on the leaf. “Little girl,” she said, softly “are you awake now?” Mabel did not answer, but just stared in surprise at the tiny person. “Are you awake?” the fairy repeated.

“I – I don’t know,” said Mabel, slowly. At least I think so, but what are all these little things and all the lovely lilies here for?”

“We are water-lily fairies,” answered the fairy, “and we were going down the river in our flower boats to the great dance of all the water-lily fairies, when this big stone stopped us, and we are going to be so late—”

“And we thought,” interrupted another little fairy,” that you would move it for us.”

“Oh, course I will, if I can,” cried Mabel, and she pulled off her shoes and stockings and stepped into the water. She pulled hard at the big stone, and at last managed to pull it to the side. “Oh, thank you so much,” said the fairy, gratefully. “Would you like to come with us to the dance, instead of lying here?” What? gasped Mabel. “Come to a real fairy dance? Oh, may I really? “Yes, really; come along. Step into this lily boat,” answered the fairy, taking her hand.

Mabel found she could sit quite comfortably in the lily boat, it was so nice and soft. They sped swiftly on for a little while down the river, until they came to a deep pool. The fairy took Mabel’s hand and stepped out on to a broad leaf, and blew the faint whistle Mabel had heard before, and all the fairies stepped on to the leaves of the flowers. Mabel looked at the water beneath her, and wondered what was going to happen. Again, the whistle blew, and immediately leaves and fairies sank below the water to the bed of the river. Strange to say, Mabel was not at all frightened, but delighted at the lovely flowers, grass, and stones at the bottom of the river. “Come dear,” said the fairy, as she jumped on a fish's back, “jump up behind me.” Mabel did so, and soon found herself flying through the water.

After a little they stopped at a lovely garden under the water, and Mabel and the fairies got off the fishes, and went into the garden. There were many more fairies in this garden, and all were dressed in green and gold, and even Mabel had a gold and green dress on and was quite as small as they were. Soon they began to dance, and Mabel danced too. In and out she whirled among the mass of green and gold, and oh, how she did enjoy it. They danced for a very long time, until the fairy by whom Mabel had been brought blew her whistle, and all sat down on the grass and drank honey dew out of lily cups.

Soon, however, the fishes came back, and all the fairies said good-bye to each other, and sped through the water, and all went home on the fishes. Soon the fish that Mabel and the fairy rode on came up to the top of the water by the tree under which Mabel had been lying.

“Good-bye now, dear; watch for me often. I will come to you again soon. Here are the lilies you wished for,” said the fairy.

“Oh, the lovely lilies. Oh, dear fairy, I have enjoyed myself so much. I don’t know how to thank you. But do come soon. Good-bye.”

Mabel watched the fairy disappear through the water. She picked up her hat and ran to the house. She burst into her mother’s room and told her about the fairies and the dance. “And I’ve got you these,” said the little girl, eagerly holding up the water lilies.” “Oh, aren’t they lovely,” said her mother. “But darling you mustn’t lie in the hot sun again; it has made you fanciful.” But Mabel was too excited to notice what her mother said.

Dorothy Stirrup, Hawthorn, Dukes Brow, Blackburn

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, 22nd September 1906

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

back to top

The Adventures of Billie Blue-Bottle

I don’t know why flies are so despised in the house where I first made my appearance., but every time we were seen flying about or singing you’d be sure to hear someone say, “Oh! those horrid flies.” We didn’t at all understand why we should be called “horrid,” for really we are quite as pretty as those huge animals called “men.”

I don’t know why flies are so despised in the house where I first made my appearance., but every time we were seen flying about or singing you’d be sure to hear someone say, “Oh! those horrid flies.” We didn’t at all understand why we should be called “horrid,” for really we are quite as pretty as those huge animals called “men.”

One day I was taking a quiet view of the garden out of the cosy dining-room window, and humming as I crawled up and down, when I heard someone exclaim, “Flies again! little beasts!” and a hand was put over me. Oh! how dark it was in that huge hand. There was hardly any room to breathe, and I was so frightened. “I’ve got it alright,” said a voice.

I was getting hotter and hotter in my prison, when, hurrah! I saw a tiny stream of light coming through a space between the fingers. Creeping cautiously up to the hole, I managed to squeeze quietly through. How glad I was to find myself free. I flew straight up to where my friends were and told them about my capture. “Do come and help me to annoy him,” I cried, “It was so hot and horrid in that giant’s hand,” and they all came, for none of us loved the people in that house very much, for heaps of our race had been killed by them.

We flew down and went to the window to consult as to the best way to tease him. “I should think singing would make him angry,” I said. So we sat down on the window sill and began to sing. “Buzz,” I began. “Buzz-buzz,” sang a second. “Buzz-zz-z-z,” we all sang.

“Oh, dear, those horrid little beasts again, I can’t read because of their row,” said the angry voice. We looked towards the speaker, and there we saw sitting in front of the fire, a huge boy, reading, with one hand closed up as if unconscious of my escape. “Buzz-buzz-zzz,” we sang. The boy jumped up angrily, and rushed frantically up and down the room after us, but in vain, he could not catch us. “I just can’t catch them,” he panted, sitting down again.

“Come along, we’ll tease him now,” I cried, settling on his nose and tickling with my legs and wings. My brother crawled all over his face, and, oh! how we all tickled him. Then we had a concert on his ears. After that we had an obstacle race over his nose, eyes and mouth, and I won.

“Oh! good gracious! Aren’t they fearful!” he groaned, and he strode out of the room; in a few minutes he came back and sat down quietly. “Now for some more fun,” I cried, and immediately began to tickle him. Finding he did not mind, I sat down on his book to have a better look at him, when all at once a tremendous stream of water was received on my body. Oh! how cold it was, and how it hurt me, my new blue coat was complexly spoilt, my legs were helpless, my lovely wings hung limp by my dripping sides, and I was nearly blinded. At last I managed to totter on to the carpet where heaps of my friends lay in exactly the same state as I was. “Oh! those giants are cruel,” said one feebly, “I’m almost killed.

“Ha! Ha!” laughed the orgre. “It was fun.”

That night a council of flies was held, and we arranged that as soon as the invalids were better we would remove them from the house of such cruel people. I feel much better now. Good-bye. I’ll tell you some more some time.

Best love,--Billie Blue-Bottle.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday 27th October 1906

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

A Tale Of A Camera

The Fairy of the Fir Forest

Master Mouse

The Haw and The Hip

A Tale of a Camera

Everybody was mad about cameras. Everybody had one, and everybody carted them about. In every nook of the school garden was a girl with a Brownie l, tucked under one arm, and a packet of “negs.” On a printing- frame under the other. Everybody “snapped” everybody else unawares and out of every book fluttered some photo or “neg.” The cameras, Brownie l.’s, were considered as “ducks,” “darlings,” pets,” &c. but a Brownie ll. Was looked upon with a sort of awe. No one had one; every one wanted one. At last a girl, Loreta (Laurie for short), did get one from her brother, who was getting a better one. She was delighted, but the others weren’t. The Brownie I.’s dropped off a wee bit, and the girls stared enviously after Laurie as she marched off alone with her Brownie ll. She was awfully proud of her ll., and wouldn’t let any one look at it. She took crowds upon crowds of photos, and the next week tied her “negs.” up in a bulky parcel, and despatched them to be printed and developed. The whole school waited in suspense for the arrival of the photos. Laurie was left to herself. She didn’t mind; she spent her time in studying photography and in the use of Brownie ll. She walked about with her head in the air, and regarded the girls with a lofty indifference. They had only l.’s, she had a ll. She had vague dreams of photo fame, and bought about ten Brownie ll. films. The photo shops grew accustomed to the schoolgirl with the dark hair and triumphant face who entered their shops and said loudly and in a still more triumphant voice: “A Brownie ll. film, please,” or “ A packet of Brownie ll. printing paper,” and the people stared and turned round to look at the dark head and the jaunty sailor hat, flaunting the school colours, with a camera strapped over her shoulder. At last a parcel came addressed to

Miss Loreta Manley,

Heydon House School,

“Hinchley.”

Laurie went proudly up to receive it, and hugged it close as she glanced witheringly round on the meek possessors of the Brownie l.’s. She rushed away to her own wee room, and eagerly tore open her parcel. The photos fluttered out, and she snatched them up and gazed at them. Alas! – alas! On the first photo was a face on the top of a tree, the next was a hand of about three feet, with the end of a skirt where the head should be. Laurie threw them from her. What had happened? The Brownie ll. must be mad. Never had she seen photos like that before. Hot tears rushed into her eyes, and she sobbed passionately. The tea-bell clanged three times before Laurie tip-toed in, with her hair tousled over her flushed face. The girls smiled as they saw Brownie l. strapped in the place of the ll. Laurie came back into favour again, but beware, never mention

a Brownie ll.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph,18th May 1907

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

On the side of a great, green hill, nestling among the oaks, stood a tiny white cottage. It was low and had only one window on either side of the door. No other dwelling was near it – it was alone on the mountain. A little child was in the gay garden of the cottage, playing among the sunflowers and bright, sweet peas, and her bare, brown legs twinkled in and out among the tall stems of the sunflowers as she ran from one flower to another burying her little brown face among the masses of sweet peas.

“Morva! Morva!” cried a shrill voice in Welsh. “Come, child- take these flowers to the town; they are lovely today and will fetch a big price.” And a woman came into the garden with a basket of flowers, which she gave to the little girl. Morva, after saying goodbye to her mother, set off along the narrow, stony path, singing as she went.

In a little while she entered a huge fir forest. Everything was grey and still, the sunlight seemed shut out, and Morva felt just a tiny bit frightened as she walked among the tall, straight trees. She looked up and down – no one was in sight. Generally she met some old Welsh women on their way to the big town, but today she was alone in the dark, weird forest. She grew more and more frightened as she got deeper into the forest and fancied she saw the “little people” peeping out at her from behind the trees. She began to sing, but the sound of her own voice frightened her, so she ceased. The little girl went on and on till suddenly she heard a soft, sweet sound, like the call of a bird. Again and again, she heard the low, clear call, but no bird was to be seen. She followed the sound till it seemed quite close to her and suddenly there stepped from behind the trunks of the grey trees, a little, old woman, in a red cloak and tall black hat. “So, you have come,” she said in Welsh. Morva did not speak. “I have waited a long, long time for you.” “For me?” said Morva in surprise. “For you!” said the old woman. “Now, come with me,” and she put out a long bony hand and took the child’s little brown one. “But” said Morva, “I am going to the town to sell flowers and mother ____”. “Mother will understand,” interrupted the old dame as she led the way along a still darker path.

It was late in the afternoon when Morva had started for the town and now night began to steal through the trees. Morva caught a glimpse of the stars as they twinkled in the dark blue sky, when all at once the old woman stopped, and gave the low call that had brought Morva to her. Three times she called and as the last call died away lights began to twinkle far away among the trees. Nearer and nearer, they came, lights of every shade and colour, all looking as if they shone through gauze. So near they came that Morva saw that little beings dressed in the colours of the lights, bore them on willow wands. Morva clapped her hands with delight as they ranged themselves in a ring before the old woman and herself. But imagine her delight when the tiny fairies began to dance, swaying the beautiful lights gently to and fro, to the time of the sweet, low songs they sang meanwhile. For a long time they danced, till, with a sign from the little woman, they withdrew to a grassy mound. Again the old woman called and Morva waited to see what happened.

There came a rustling, a swaying of branches and a crackling of twigs and in a minute thousands and thousands of tiny elves stood before them. “Bring the cushion,” cried the old woman. They disappeared but reappeared instantly with a large cushion of rose leaves and thistle-down. “Come,” said the fairy (for indeed she was one), and taking Morva’s hand she and the wandering little girl lay down on the cushion. “Ready!” and immediately the cushion soared into the air over the tops of the fir trees. “Look!” said the fairy and pointed to the world below. Morva peeped over the edge of the cushion and saw far, far below her the dusky fir forest, the twinkling lights of the town, and above all, the one tiny light in the cottage on the side of the hill. They drew near the stars now and Morva noticed one particularly bright, larger than the other and wished she could enter it. The cushion came nearer and nearer to it, till it stopped right in front of it. The star seemed to be made of silver, so bright that the little girl had to shade her eyes to look at it. The old fairy pushed open a small silver door and they entered.

Never had Morva imagined anything could be so beautiful. Everything seemed to be of a soft silvery-blue colour. There were tiny silver-blue houses, with lovely gardens and a blue river flowing peacefully along, dotted over with silver boats. The fairy called softly, and she was answered by merry cries and out of every house came children eagerly running to greet her. “You have come at last,” they cried as they crowded round her. They were beautiful children; all dressed in dainty silvery-blue. “These,” she said, turning to Morva after she had greeted them, “are the star children.”

“So, this is Morva of the Hills,” said a star child; “I have often peeped down at her playing in her garden. “Now,” said the old woman, “we will go in a boat.” And as she spoke a silver boat drew near. The children crowded in after the fairy and the boat glided through the clear water. “Sing- do sing!” cried the children and so the old woman sang. Her voice, clear and sweet as a bell, rang over the water. She sang of fairies, hills and children; wonderful songs of the sea and of mermaids; and at last, when her voice died away, not one child moved. “Morva,” she said, “we must go, the dawn is coming.” They bade goodbye to the children and went out of the star and lay down on the cushion. In a very short time Morva found herself standing in front of the cottage. She ran into the house. “Morva! Morva! Back!” cried her mother. “Where have you been? I thought you were lost, though something told me you were safe.” Morva told her all about the old woman. “That,” said her mother, “was the good fairy of the fir forest.” “Oh! Mother!” cried Morva, “look!” and she showed her a little silver coin suspended round her neck. “A lucky penny,” cried the mother; “nothing will ever harm you while you wear that.” Morva was delighted, but never again did she see the “Fairy of the Fir forest”.

Transcribed by Shazia Kasim

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday September 21st 1907

Master Mouse

All was dark and still, except for the sound of red ashes falling through the bars of the fire-grate. Master Mouse popped his little grey head out of his snug hole and looked about. Yes! all was safe; he must get some food for they – that is his tiny brothers and sisters – had fed on a corner of carpet for a week and never a scrap of cheese or candle for desert! It was awful! Oh! it was quite plain that Master Mouse must go in search of food. So with a sigh (for Master Mouse was lazy) he crept out and stole across the hall. He was getting on finely, when, to his great fear, he spied Miss Tabby Cat stretched comfortably in front of the dying fire. She was fast asleep, never dreaming of the plump little mouse so near to her. Master Mouse waited a little, to see if she moved; it would never do to go back without anything. Miss Tabby Cat slept on, so he scurried down the passage and made for the pantry door.

Here was another difficulty. The space between the pantry door and the floor was far too small for Master Mouse to squeeze through, and he crept disconsolately down the passage, his dreams of cheese and candle shattered, and his long tail (of which he was very proud) draggling along behind him, when he saw a little hole in the side of the panelling. “Perhaps,” he thought “it leads to the pantry.” And his hopes revived again, as he popped into the hole. He found himself in a very, very narrow passage. So narrow that he could hardly squeeze along. But he struggled bravely, borne up by the visions of a feast. After wending his way, very painfully for a good while, he heard the far-off sounds of squeals and squeaks. Perhaps they were some friends, enjoying themselves, and he would be able to get something after all without working for it. You see Master Mouse was lazy.

The sounds grew louder and louder, and Master Mouse hurried along, till at last he turned a sharp corner, and came full upon a crowd of mice, gathered round little heaps of meal, bits of candle, lumps of cheese, and anything else that a mouse delights in. Master Mouse’s mouth watered as he eyed the luxuries, and at once he advanced to a solitary piece of candle and began nibbling. After he had eaten half a candle he started on the cheese, and it was not until he was halfway through a heap of this that the other mice noticed him. Then there was an uproar. They rushed on him, squealing, squeaking and uttering all the noises possible for angry mice to make. They bit him, and scratched him, tore his whiskers out, pulled his fine tail, and when at last they stopped for a second to refresh themselves for a fresh onslaught, it was a wreck of Master Mouse who squeezed up the narrow way with a dozen or more of his enemies at his heels. On and on he struggled, tired out, aching all over and, he was glad to find a wider passage where he could run with ease. After a little while the sounds off his pursuers died away, and Master Mouse took a rest in the passage and looked round him. He had not the faintest idea where he was; he had only been out food hunting once before and had never got into narrow passages under the floor before. How was he to get out? Wherever was he to get food for the others from? Well! they would just have to live on carpet a little bit longer. He had had a good feast, and so he was satisfied.

He got up and trudged wearily along, when a faint odour of toasted cheese met him. He hurried on as fast as he could and soon came out of the hole, and there right in front of him, was a little box with shining bars across and oh! what good luck! a big piece of toasted cheese hung temptingly near. Master Mouse jumped on the top of the box and tried his very best to reach the luxury. But in vain; he could not touch it; he pawed the bars fiercely, but it was no use.

His tail dangled near the cheese, through the bars; he stuck his fore-paws through trying as hard as he could to reach the cheese. All at once there was a snap. With a squeak Master Mouse tumbled off the box and fell with a thud on the ground, without his tail.

Poor Master Mouse! His tail was the pride of his life. Was it not the longest, finest tail in the neighbourhood? At least, so he thought. With one terrified glance at his fine long tail lying in the box, he scurried heedlessly down the corridor.

Master Mouse seemed bound to meet misfortune on this night, for, there in front of him, was the huge bristling shape of Mistress Tabby Cat. She was hungry, and she licked her lips as she eyed the plump little mouse cowering before her, and thought how nice he would taste, but, as Master Mouse had done, Miss Tabby Cat “counted her mouse before he was caught”. For Master Mouse, alive to his danger, warily slipped past her and rushed on, with the angry cat after him. She did not run her fastest, for she was sure of catching him. How dare the little creature try and escape? She would punish him for this; she would keep him in fear of his life longer before she made a meal of him.

But Master Mouse was a fleet little thing, and he dashed across the hall, with the cat, anxious now, bounding after him. She made one blind spring at him only to bound against the wall and then found that Master Mouse had disappeared into his snug hole. Fancy, beaten by a mouse! She lay down outside the hole, but he never made an appearance. Nor was Master Mouse fit for a long time to again go food hunting, and when he did, he was a wiser and sadder little animal, and took great care to keep away from the house where the cheese was hung, and also other people’s feasts.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, 12th October 1907

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

The ground and hedges were all covered with snow, hardly a dot of green was to be seen anywhere, but flaunting its scarlet head over the dazzling snow, waved a Hip, and by its side hung a crimson Haw. They quarrelled the whole day long about their brightness of colour.

“Why, I am far away more beautiful than you, little stunted Haw,” sneered the Hip.

“Oh, you may think so,” replied the Haw, “but opinions differ. Now just look at my perfect shape, my glorious colour, my nice black hat.” “You have not a long green stem like I have,” said the Hip; and so, they went on day after day.

One day there came an invitation for them both to a dance held at moonlight underneath the oak tree. “Now,” said the Haw, “this will be a good chance of showing off my bright red coat.” And he called the caterpillar out of his snug bed and had him polish his coat until he could see himself in it. So the sleepy caterpillar rubbed and rubbed, and the coat grew brighter and brighter, until the caterpillar caught sight of an ugly black head and two great sleepy eyes “Goodness gracious! What’s that?” he cried. “Oh, that’s you,” said the Haw. “Go on rubbing.” But the caterpillar was lying in the snow panting and struggling to crawl away in case the strange creature he had seen should come after him, so the Haw had to be satisfied.

The Hip looked quite dull beside him, and he racked his brains to think of a way to make himself shine. At last, he had an idea. He would stick his head in the snow, and so he would get bright. So he stuck his pretty head into a heap of snow. It was very cold, but he thought of the brilliant Haw, and bore it bravely. Then he admired himself in a drop of water. “Oh!” he thought, “the Haw looks pale beside me. How I shine! Won’t he be jealous? I shall be the handsomest at the ball!”

All the time the Haw was admiring himself in another drop of water, when suddenly a shadow fell across the snow, and looking up, they both saw a little Robin, eyeing them hungrily. “Chirp!” he said, “I’ll have the brightest first.”

The Hip glanced triumphantly at the Haw, who returned it with interest. Now they would know who was the brightest: they did not think of the danger. Robin drove his sharp little beak into the Haw and pecked away all the lovely red coat and left only one tiny bit clinging to a bare, brown stone. Then he advanced to the Hip and took a good bite until the Hip had shared the same fate as the Haw.

“Chirrup!” he sang after he had finished. “I should never have seen them but for their bright red coats and because they waved so high trying to get above each other.” And the bits of Haw and Hip shook mournfully in the wind.

Published in The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday October 19th, 1907

Transcribed by Shazia Kasim

The Marigold and the Violet

Rosebud & Pukaboy

For the King

The Two Dragon Flies

Robin Redbreast

Once upon a time all the flowers were equal, and all grew in the same place – the roses and violets, the orchids and daisies all grew side by side.The Orchid was the Queen of Society then, and the Pink Rose, her relations, and all the other flowers were members of society. The Spotted Orchid, being the queen, was the only flower that had a maid to wait on her. Her maid was the little Purple Violet, who had no desire to be in “society,” and had offered herself to the Orchid for a maid.

Purple Violet was very humble, and whenever she was not curling the Orchid’s handsome leaves or gathering honey for her, she ran away to hide herself by the cool, green moss, and just sing happily to the water beetles as they darted over the top of the water.

One of the most important members of society was handsome Sir Marsh Marigold, and, as the Bee had whispered to the Violet, it was hoped that some day he and the orchid would lead society together.

One day the Dragon-fly, who, as I suppose you know, is the flower’s messenger, brought invitations from Sir Marsh Marigold to a moonlight ball to be held under the weeping willow that night.

“Quick!” cried the Orchid, sharply, to Purple Violet Curl up my leaves! Draw me some dew! Go and get some paint and fresh up my spots! Quick! Oh! how slow you are. I shall never be ready in time.” Poor Purple Violet rushed hither and thither, trying to do all that her mistress told her at once.

She could not find any paint, then there was not enough dew for the queen to bathe in, and then the Orchid’s leaves persisted in curling up the wrong way. At last the Orchid got so angry that her spots really blazed, and she cried out in a terrible voice, “You shall not go to the ball to-night, you are too slow and stupid for anything; you shall stay at home, and come at the end of the ball only, to bring my cloak.”

At this poor Violet’s tears fell, because she did so love to see all the gay flowers, with their beautiful dresses, dancing in the moonlight.

After a little while Orchid was dressed in all her best, and she set off on the butterfly’s back for the ball. Soon the sound of music and dancing came creeping to the little Violet as she hid in the moss. It was really too tempting. Violet could not resist one little peep. So she crept up to the weeping willow and peered through the branches. There was Queen Orchid and Sir Marigold talking together not far from her, and there, at the other side, was My Lady Rose, eating honey with Duke Hyacinth, and there ____ Oh! the Orchid had seen her! She and Sir Marsh Marigold were coming towards her! Whatever could she do?

“How dare you!” cried the Orchid, trembling with rage. “How dare you come to the ball when I forbade you to come? I shall report you to Judge Beetle for disobedience.

The poor Violet could not say a word. She was so terrified. Then Sir Marigold stepped forward. “Madam! Madam!” he said. “Don’t be so angry with your little maid. Don’t ____”

“Sir Marigold,” interrupted the Queen,” “it is really too bad of her. I was obliged to forbid her to come to-night, much against my will. She is so disobedient and aggravating. I really cannot help-p it, Sir Mari-g-il-“ and the Orchid fell in a fainting fit right into Sir March’s arms.

Purple Violet was very much distressed at the effect her conduct had had on her mistress, and did all she possible could to bring her round. At last she revived, and was on the point of sending Violet home, when Sir Marigold interfered and said that as long as she was here she might as well stay, and he led her away to dance with him.

The Spotted Orchid curled her leaves contemptuously and tried not to look angry. Sir Marsh stayed with Violet all the evening, and gave her a personal invitation to a dance he was giving in a few nights, and of course little Violet was delighted and went home very happy.

The Orchid after all this was very unkind to her little maid, and when she heard of the dance, she said that on no account could Violet go, and the poor little flower crept away to the friendly moss to cry.

Days went by. On the night of the dance the Orchid went off to the ball, leaving Violet at home. Violet sat swinging on a long stalk, crying to herself and gazing at the moon, for she dare not go again without permission, Orchid would be sure to dismiss her, so she sadly swung to and fro on her stalk beside the river, and by-and-by she fell asleep.

“Violet, Violet,” someone called, and the flower woke up hastily to find Sir Marigold standing before her. “Come quickly,” he said, “to the ball; we are waiting for you,” and before she knew what was happening, she leading to the ball with Sir Marigold, and the Orchid was dancing fiercely behind her, all her spots flaring with anger.

When all the leaves were resting on toad stools, about the middle of the ball, Sir Marigold led Violet up to the Queen and told her that she was going to marry him, and gave her and all the flowers an invitation to the wedding. Then the Orchid jumped from her seat and angrily that she would never come to their wedding, and that if Sir Marsh Marigold chose to marry a waiting-maid, he should have his title taken away from him and should no longer be a member of the select Society. After this speech the Queen of Society haughtily withdrew, and the rest of the flowers went with her, stepping past Sir Marigold and Violet with their heads in the air.

That morning at dawn Sir Marigold, with his wife, the little Violet, wandered out of the garden of Society into the common fields and meadows, and they settled by the riverside, and were as happy as could be living alone, far away from Society. And that is the story of how the Marigold and the Violet became field flowers.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday 21st March 1908

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

Two little mushrooms grew side by side on a bank by a stream. Under these little ‘buttons’ lived two little fairies, Rosebud in one and Puckaboy in the other. They were great friends, these two, and every day they went together to draw water to play by the brook and were as happy as the day was long. One day, while they were sitting on top of the smooth, white mushroom, each under the shade of a lady’s mantle leaf, chatting pleasantly, the old grasshopper came up. “Good morning,” said Rosebud politely, “I hope your gout is better.” “Getting on nicely, very nicely, thank you,” clicked the grasshopper.

Two little mushrooms grew side by side on a bank by a stream. Under these little ‘buttons’ lived two little fairies, Rosebud in one and Puckaboy in the other. They were great friends, these two, and every day they went together to draw water to play by the brook and were as happy as the day was long. One day, while they were sitting on top of the smooth, white mushroom, each under the shade of a lady’s mantle leaf, chatting pleasantly, the old grasshopper came up. “Good morning,” said Rosebud politely, “I hope your gout is better.” “Getting on nicely, very nicely, thank you,” clicked the grasshopper.

“And how are you young stay-at-homes getting on?” he inquired. “Still as contented as ever? Why at your age, I was always on the jump, always going somewhere new, and looking out for something fresh. Why, I went to see the world, I did, at your age.”

Both fairies tried to look very interested. “Yes!” he went on, “the world’s a very wonderful place, full of beauty and green grass. This,” he waved his leg contemptuously round. “This is nothing to the world. Go out, both of you, and see it. I would if I had the chance, and believe me, you won’t be sorry for it,” and the old grasshopper went off.

The two were very quiet for a little while, then Rosebud said, with a sigh, “suppose we try it. I’m rather tired of this place.” Puckaboy shook his head.

“No, Rosebud,” he said, “I don’t think we’d better; you don’t know what other things there are in the world besides green grass. Let’s stay at home.”

“Well,” said Rosebud decidedly, jumping off the mushroom, “if you are not coming with me, I am going by myself.”

That would never do. Puckaboy could not let her go alone.

“Of course I’ll come with you,” he said. “When are you going?”

“Tomorrow,” she answered. “Get something for us to ride on, Puckaboy, dear, for I suppose the world is big.”

The next morning, just as the sun rose, Puckaboy was waiting outside Rosebud’s mushroom with a pappus of a dandelion (one of the piece’s of a dandelion ‘clock’).

Rosebud and he were very soon mounted. Puckaboy in front and Rosebud clinging on behind. There was a little breeze, so all went well for a time. And all that sunny day the two skimmed merrily over the heads of the gay summer flowers, as happy as could be. Just when it was growing dusk, the wind came roaring up from the east. Puffing and up and down. A great crash came, and then a lull. Another flash, and then the same awful

noise. Rosebud flew from one flower to another, crying, terror-stricken, to let her in. But all the flowers were fast asleep, their heads drooping almost to the ground. The storm raged on. The poor fairy threw herself down on the ground and buried her face in the grass. By-and-by the thunder stopped, then the rain came down in torrents, but Rosebud did not feel it, for worn out by fear and excitement, she was fast asleep.

Next day the sun came up as rosy and jolly as ever. He saw the poor little fairy lying on the damp grass and being a kind old sun, he put out all his strength to warm her and dry her wet wings. Very soon a little fairy came wandering through the grass. He looked very sad and disconsolate, and he searched very carefully about him as he walked. Suddenly he rushed forward. “Rosebud! Rosebud.” The little fairy woke up. “Oh, Puckaboy, are you here. I’m so glad to see you again.” And indeed, they were delighted to see each other.

“Oh, do let us go home again,” said Rosebud. “The world is a horrid place, Puckaboy. Let’s start out now.” And home they went, and they reached their own little mushrooms just before dusk. “After all,” said Puckaboy, when they were comfortably settled that night, “after all, there’s no place like home.”

And Rosebud heartily agreed.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday September 5th, 1908.

Transcribed by Shazia Kasim

Over the great brown hill went little Mistress Margery, down by the stream into the cool woods, under the golden brown shade of the trees; over the rustling leaves, on and on she went, for it was a long journey from the church to her father’s house.

And to-day she had to make it alone, for Charity Prane, her old companion had stayed with Friend Kirken to dine. So it happened that she was alone, waist high in the yellow bracken, this bright September Sabbath.

She made a pretty picture as she stood there in her simple grey gown and white folded kerchief; her soft curls peeping out from her stiff white bonnet, surrounded by all the glories and harmonies of early autumn.

But Mistress Margery was not thinking of the beauty around her. Something seemed to trouble her as she walked slowly along; for there was a wistfulness in her blue eyes, a sadness lurking round her mouth which did not usually belong to this happy little Puritan maid.

She was thinking of the King - King Charles. Thinking of his haunted life, of his imprisonment, and of his poor young children. Why did men harass him so? Why was it her father and Friend Hubert spoke so often in whispers? Why did they look so grim and stern when she spoke of the King? That brave King, so handsome and gallant, whom she had seen once, long ago, as he rode laughing and jesting through the little village.

Did they mean some harm against him? She had seen them giving orders to a band of Puritan soldiers the other day. She knew they were going to fight. But for, or against the King. Oh! surely, not against him!

Little Margery in her secluded home knew hardly anything of the war raging in the country. Her father, a stern Puritan, would not speak of it to her. Charity Pane did nothing but mumble, “Lord, save us!” and shake her old head in reply to her questions. Yet, from the little she had heard Margery had grown to love this King, and all her girlish sympathies and sorrows were for him.

Margery had reached the little glade now, and had stopped to lean over the well. How beautiful the world was! How golden the bracken! How lovely the red brown trees! And the King was shut away from all this. Poor, poor King. Margery’s eyes were filled with tears. Hush! What was that? A footfall surely. The leaves rustled, a twig cracked, and a man leapt out from the bracken, his hands raised as if to implore silence. She choked back a cry and waited.

“Your pardon,” he said softly, “I am sorry I startled you so.”

She noticed his dress, rich and flashing with jewels, his great sword and scarlet sash of the cavaliers – “The King?” she cried. “Nay, nay sweet maid, but one of his most loyal servants,” and he bent low to the ground. “I beg you,” he continued hurriedly, “for the love of God show me a safe hiding place. The guards are after me! I do not know this country! God knows I do not ask it for myself, but for the King.”

“For the King,” she whispered. “But my father, my father, what will he say? He does not love the King as thou and I.” Alarm crept over her face.

“You love the King?” then help me to save him! I tell you they will kill him. Yes, kill him-oh! but there is not time to tell it now."

“I will help thee,” she answered, “and the King.”

Quickly she led him to a hiding place, a place of which she alone knew, which she had found long ago in her wanderings. It was a small undergound passage, small and ruinous. The entrance was hidden by boulders, overgrown with bracken and brambles. “Canst thou move them?” she whispered anxiously. He did not reply, but fought with the stones. At last he forced a passage and leapt down.

“You cannot replace it,” he said with a look of despair. And indeed she could not.

Suddenly terror crept into her eyes, “Some one comes,” she cried. The despair deepened on his face. “The King,” he muttered aloud he said “Go! Go quickly. You must not be seen with me!”

“No,” she said firmly. It is too late.” Seizing the nearest bracken she tossed it over the aperture, more and more she threw on, until it seemed like a heap of dead fern so often seen in the woods. “I shall stay with thee,” she said as she sat on the misplaced stone and carefully spread her gown over it to hide the new earth which clung to it. In vain he implored her to go.

“Hush,” she answered, “it is for the King.”

Steel helmets began to shine among the trees, and in a few moments a band of guards were pressing up the hill towards her. Margery’s heart throbbed violently, and only by great effort she controlled herself and strove to appear calm. “Hast thou seen a King’s man pass this way?” shouted one in a hoarse voice. “No, sir,” she answered steadily.

“If thou’st telling me a lie I’ll knock that-

“Leave her alone, Dick,” interrupted one, good naturedly, “Cant not thou see how thou’rt frightening the child.”

“Aye, forward, lads forward; ‘tis but waste of time to question babies!” shouted another.

“Once more, lass, hast thou seen anyone pass this way?”

“No, sir”

“Are there any hiding places near?” “There is one – the hollow at the end of the wood.” She directed them quickly; they went at last, stealing away among the bracken. For a long time neither moved. Margery’s conscience was pricking her now. She had not spoken the truth. She had told a lie, as that soldier said. Her soul shrank from it. An untruth seemed the blackest of sins. What should she do?”

“Is it safe,” came an anxious whisper.

“Yes,” she answered.

In a few moments the cavalier was kneeling at her side. “How can I thank you?” he said, pressing her hand to his lips. “My maid, this day you have saved his Majesty’s life and mine. I cannot find words to thank-you, my heart is too full of joy and hope. But for you little maiden, I should be dead now, and the King in deadly peril. But you have saved us, my King and I.”

Margery’s face was covered with confusion. “Sir,” she said softly, “I do not even know thy name.”

“Rupert.” He answered.

“Prince Rupert, the robber?” she cried.

“Aye, so they call me. Nay, rise,” as she fell on her knees, “and tell me, my brave maiden what is your name?”

“Margery Maine,” she said, simply.

“Then, sweet Margery, take this is remembrance of the King and I.” He unfastened a great jewel from his laces. “Nay, do not refuse, it is for the King. Adieu, my little saviour.” After kissing her hand many times he dropped among the bracken and was gone.

“Fare thee well,” she called and stood there with happy tears in her eyes and the jewel flashing in her hand. She had served her king.

Years afterwards, when Mistress Margery grew older, she thought happily of the jewel as she showed it to her little ones, but that untruth lay heavy on her innocent soul, and gave her many unhappy twinges of conscience.

The Two Dragon-flies

Away down at the bottom of the pond two queer-looking little objects were wallowing together in the thick mud. They really were the ugliest, funniest little creatures imaginable. Both had think dark bodies, heavy heads, and great sleepy eyes which seemed to be too big for their bodies. They crawled slowly and lazily along.

‘I say,’ said the gentleman grub, ‘Don’t you think we’d better be getting married soon?’

‘I suppose so!’ answered the lady grub, blinking her great eyes.

‘Well suppose we get married the day after to-morrow,’ said he.

‘All right,’ said she, and all at once she went to sleep. ‘She really is getting very queer,’ said he to himself. ‘I do hope that she is all right before the wedding-day,’ and away he went to arrange matters. The Black beetle said he would marry them on the appointed day, and all the bull-heads, water-beetles, sticklebacks, and other grubs promised to come to the ceremony.

Mr Wobblyboy (the bridgegroom) was very excited, and actually ran across the pond. But the bride could not be aroused. She lay in the mud, half asleep, and took no interest at all in the preparations for the great day. Mr Wobblybob grew alarmed, she was so changed. What could be the matter with her? He grew desperate, the eve of his wedding had come, his bride had only opened her eyes once and seemed to have forgotten all about the wedding and him.

Poor Mr Wobblyboy went to bed very unhappy. In vain his friends tried to cheer him and tell him that it would be all right. He did not sleep at all that night, but just as dawn began to break the weary grub fell asleep. All at once he was awakened; someone was poking him with a stick. A great grub stood by him, his heavy head and fat body shaking all over with excitement.

‘There,’ he said quickly. ‘She’s gone off.

‘She’s off- she’s---'’Where? Where? cried poor Wobblyboy.

‘Off! Off! Half-way up the lilyroot! Come on! Come on!’ Away went the two at full speed, poor Mr Wobblyboy wringing his hands (or rather his legs) in agony.

‘I knew something would happen. I knew it would,’ he kept moaning, as he went along.

A crowd of grubs had gathered round the lilyroot, and were watching with great interest the progress of another grub, as it slowly but surely clambered up the slender root. ‘Yes, yes, it is she,’ cried miserable Mr Wobblyboy, as he gazedupwards. ‘Oh! What shall I do? What shall I do? To think that she should go off and leave me like this. To think – ‘her his emotion became so great that he over-balanced himself and flopped on his back in the mud.

All his friends rushed to him, and by a great deal of pushing and struggling they at kast managed to set him firmly on his legs again. ‘Poor fellow,’ they said, ‘Poor fellow.’

Wobblyboy could only lie there and stare; it had been too much for him. Suddenly he felt an overpowering desire to go to sleep . Vainly he upbraided himself for forgetting his sorrows so much. He simply could not help himself. He shut his great eyes and dropped into a deep sleep. By-and-bye he awoke, feeling very queer and sick. What could be the matter with him? Something seemed to be compelling him to get out of the pond. The lilyroot swayed near him, he crawled trembling towards it. And in a few moments much to his own surprise, he was a good way up it.

On and on he climbed, very slowly and painfully. The desire to get out of the water became stronger and stronger. At last he poked his great head over the surface of the water, and in a little while he was clinging to a read a few inches from the water. An awful feeling came over him, then he remembered no more.

Two pale, frail creatures were clinging to one reed. They hung there thin, colourless and apparently lifeless. At last one opened her great eyes and saw the other above her. She nearly fell into the pond again, such a horrid ugly creature it was.

She drew a long breath and stretched her wings. There was a glorious creature with a brilliant body and lovely wings. She longed to fly away over the gay green fields, but curiosity made her wait a little and see what was going to happen to that other miserable looking object by her, so she watched with wondering eyes.

By-and by he woke too, and the same thing happened to him.in a few seconds another glorious dragon fly fluttered by her. He was even more beautiful than she was.

They were astonished when they saw each other; it took them a long time to get over it. At last the gentleman spoke.

‘How glorious everything is! Suppose we fly around together and look about this beautiful place, shall we?’

‘Oh, yes, said the lady fly. ‘I should like to very much.’

So they flew away together over the beautiful, gay world. They had forgotten about their old life in the mud at the bottom of the pond. And as to him being the ugly Mr Wobblyboy and she his future bride – why! They never dreamt of it.

In a little while they got married, this time without the bride going off, and I am sure were the happiest little dragon-flies under the sun.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday 14th November 1908

Robin Redbreast

On the bare branches of the old hawthorn tree stood a little robin redbreast. He looked very dejected and lonely, his little head drooping on his red bosom, and his bright black eyes looking very unhappy. He was not chirruping gaily, as he generally did, on the fine, frosty mornings,

“Hullo, Rob,” shouted a cheeky little sparrow, “what’s the matter? Had no breakfast?”

“Oh, yes,” said Robin, “plenty.”

“Well, if you’ve had plenty, what’s the matter.” Food was all the sparrow cared about.

“It’s a great deal worse than having no breakfast, “said Robin, sadly. “I’ve lost my brother!”

“Oh, cheer up,” said the sparrow, not in the least concerned. “He’ll turn up soon.”

But Robin couldn’t cheer up. His little brother had been away two days now, and Robin had searched high and low. He was just wondering where to look for him next. He determined to look for him until he found him.

How frightened his poor brother would be, out in the wide world by himself. Just as Robin was going to set out, Miss Jenny Wren flew by.

“Good morning,” she called. “I’m just hurrying home. I’ve heard there’s going to be a fearful storm!”

“A storm,” said Robin to himself. “That’s worse and worse. Bobbie will be more frightened than ever. I must away.” He spread his wings, and away he flew over the fields. The sky grew greyer and greyer, the air was bitterly cold. “I don’t care about anything,” said the brave little bird, “if only I can find Bobbie. But, oh, if the wind begins to blow, what shall I do?”

The snow began to fall. Robin hurried on. All at once there was a great rumbling, then a fearful whistle.

“Oh!” cried Robin, “the wind! the wind!”

The great wind came rushing up from the north, whistling and screaming as it came. The trees creaked and bent before it. The snowflakes whirled round furiously. “Ha! Ha! Ha!” he roared louder than ever as he caught up the poor helpless Robin and hurled him before him on his way. “Hee! Hee! Hee!” he screamed, tossing him away up high, and throwing him down in the snow again.

Poor Robin lay there, with hardly any breath left in his body, and his little heart fluttering painfully.

But the thought of Bobbie helped him on. He got up and flew on; but, alas! Back came the tyrant wind, howling fiercely. He seized the little bird, whirled him round and round, tossed him up against a tree, then, with one awful scream, flung him again on the piled up snow and rushed by.

Robin's wing lay broken, his heart beat feebly, the snow fell thick upon him. “Bobbie! Bobbie!” he cried, tremblingly. Then his eyes closed, and the fluttering grew fainter.

“Robin Redbreast!” said a little voice. “Robin Redbreast! Come with me.”

Slowly, very slowly, Robin opened his eyes. A tiny fairy stood by him, but his eyes closed again. Then he remembered nothing more. When he awoke he was lying in a cosy little nest. Little brown elves were flying hither and thither, binding up his broken wings.

He also felt so comfortable and happy, but, best of all, there on a twig above his head chirped Bobbie!

Oh, how delighted they were to see each other again! How they did enjoy talking over their adventures! Bobbie told Robin how he had been lost, and how the kind fairies had taken care of him and kept him there to wait for his brother.

The elves home turned out to be the sweetest little place, and when Robin was better he and Bobbie were very sorry to leave it.

But they went home to a warm welcome. All the birds came out to greet them. Old Lord Owl solemnly knighted the brave Robin, and the cheery sparrow brought him a fine fat worm to show his admiration.

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, 12th December 1908

Transcribed by Philip Crompton

back to top

A Tale of Cheepy Sparrow

The Adventures of the Little Silver Elephant

The Wilful Crocus

Jeremiah Bobtail

The Baby's Adventures

The Youngest Peggy White-throat

The Further Misfortunes of Tommie Tomkins

Dewdrop and Daddy Longlegs

Billy Blun

A Tale of Cheepy Sparrow

The other day, when Mr Cheepy Sparrow was sitting leisurely over his breakfast, the postman brought him a letter. Cheepy lazily opened it, and read to his great joy and surprise-

‘Mr Sunny Starling requests the pleasure of Mr Cheepy Sparrow’s company a dinner party on Tuesday.’

‘Well, I never!’ he exclaimed. ‘Fancy, me being invited to a dinner-party – and to Sammy Starling’s, too! Dear me! Dear me! All the woodland society will be there. How important I am! I must go off and order my new dress suit immediately.’

And away he bustled to the tailor’s -W. Woodpecker. There he ordered the finest dress suit that could be made, and then bustled off home again. He called in at all his friends’ houses on the way to tell of his invitation.

He was the only one that had one.

‘I’ve heard,’ he said to one, ‘that Duchess Dove and Lady Pamela Pigeon are going. I’m sure it will be a very grand affair. What a pity you aren’t asked, isn’t it?’

He said this with such a condescending air that his friends felt as if they would have liked to kick him out of the nest.

How the time did drag! At last Tuesday arrived, and Cheepy Sparrow woke in a perfect flutter of excitement. All that day he did nothing but gaze at his dress suit and try on his new tie and light gloves.

Just as the blackbird, who stood for a clock in the woodland, called half-past seven, Mr Cheepy Sparrow stepped out of his nest, carefully dressed in his new suit, his white tie beautifully tied, and his claws tightly packed into his new kid gloves. He strutted up and down a little before his friends’ houses in order to give them a chance of admiring him, then set off for Sammy Starling’s in a whirl of excitement. In a little while he arrived, and was ushered in by Billie Bluebottle, who looked very uncomfortable in a new livery.

Cheepy bowed on every side as he advanced up the room.

‘Who is this officious person,’ said Countess Harriet Henpartridge, eyeing him all over disdainfully. Then, when told, she cried out loud and angrily, ‘I did not know, Mr Starling, that when I cam to this party I was expected to mix with sparrows!’

Poor Cheepy Sparrow felt very embarrassed, and slunk away to a seat in a corner. There the great people forgot all about him, and it was not until dinner-time that somebody spied him.

‘The idea’, cried the Countess again, ‘of coming toa dinner-party and sulking away in a corner. But, alas! I fear it’s the way with all these vulgar people – they have no manners.’ Mr Cheepy Sparrow felt very much inclined to retort that she had none, but thought it best to say nothing.

When they went into dinner, Sammy Starling discovered there was no room for Cheepy at the table. ‘Hope you don’t mind.’ He said, ‘awfully sorry. You can dine after with Bluebottle the butler.’

Cheepy Sparrow almost cried with mortification, and was just going to ask Starling if that was the way he treated his guests when the Countess broke out again:

‘Indeed, it’s a very good thing, for I should never have suffered myself to eat at the same table with such a vulgar person.’

Poor Cheepy tried to stammer out something, but the words stuck in his throat, and he was obliged to go out of the room to hide his grief and vexation.

In the hall he met Billie Bluebottle, ‘Get me my hat,’ he cried. ‘I won’t stay in this house another minute.’ ‘Cheer up, cheer up, old man,’ said the Butler. I know what it is – I know what it is. Haven’t I had to stand it for four weeks. I’d escape if I could, but, bless you, he’d find me out – he’d find me out,’ and with this he went into the dining room. Cheepy Sparrow set out for home, wishing over and over again he’d never come.

‘It will get out all over town,’ he said, bitterly, ‘and everybody will crow over me and despise me.’

He went on thinking over what had happened, when suddenly he heard somebody calling for help. A minute later after a great bird flew by with a small bird in its mouth. The little prisoner fluttered and struggled. It must have seen Cheepy, for it called, ‘Mr Sparrow, Mr Sparrow! Help me, save me.’ Now Cheepy, though so conceited and proud, was very brave. He darted after the bird, which he found to be the Hawk, a dangerous enemy of his.

Cheepy was determined to make him drop his prey. He pecked at him with all his might, and fluttered before his eyes so that the Hawk could not see where he was going. He annoyed him is every possible way. At last the angry Hawk dropped his prey and swooped down on Cheepy, Cheepy calling to the other bird to make off as quickly as it could, darted away in the darkness.

On and on he flew. He could hear the swish of the Hawk’s wings behind him. His little heart beat violently, his wings began to lose their strength. All at once he remembered an old trick he had once heard of. He made a wild dart forward, then dropped noiselessly and suddenly to the found. To his intense relief he heard the Hawk fly on above him.

A little while after a weary and ragged little sparrow arrived in the wood. To his surprise a great crowd of birds were anxiously awaiting him.

‘Three cheers for Cheepy Sparrow,’ they shouted, and he was quickly surrounded by a noisy crowd, who praised him altogether.

‘I say, Cheepy, cried Robin Redbreast, ‘do you know who you’ve rescued?’

‘No’ said Cheepy rather wearily.

There was a murmur of excitement.

‘Why, you lucky fellow, its little Princess Dolly Dove, and here is the queen coming to thank-you.’ And so it was. Cheepy Sparrow was overwhelmed with tears and thanks and gifts of the queen and her daughter. He was taken to court at once, and raised to the office of Lor High Chancellor. His heart was nearly bursting with joy. Now he could afford to smile at the insults of Countess Harriet Hen Partridge and her set.

And I must not forget to tell you that Cheepy Sparrow soon found a pretty little wife, and they live very happily next door to the palace itself!

The Blackburn Weekly Telegraph, Saturday 23rd January 1909

The Adventures of the Little Silver Elephant

The little silver elephant lay on the hard, cold ground, staring up at the wintry moon. The little elephant had never been in quite so still a place before, and he felt very queer as he watched the dark tree quiver and creak above him.

“I suppose,” he said bitterly, “I shall have to lie here for ever and ever. I don’t suppose that my lady will ever find me now,” and the poor little elephant began to cry, for he was very fond of the lady who owned him.

Suddenly, a great black beetle pounced down on him. “Hi! Move on there.” He shouted, “Stop blocking up the pavement. Can’t you see you are stopping the passage? Move on!”

“Oh! Sir,” quivered the little silver elephant,” “who are you?”

“I! Who am I? Well, I’m P.C. B. O. Beetle,” he said, pompously, “and if you don’t move on I’ll commit you to prison. What is your name?”

“Oh! Sir! If you please, sir,” said the terrified elephant, “I’m Silverboy Elephant,”

“Well, then, Silverboy Elephant, please to move on,” said P.C. B.O. Beetle, giving Silverboy a poke. “Her Majesty Queen Sally Slow-Snail is coming home from the ball now and if she sees you in the way – goodness knows what will happen. Well, I declare, here she comes. Move out quick! Make way for the Queen Sally Slow-Snail,” and the excited B.O. Beetle waved his legs imperiously on all sides, lifting poor Silverboy right off his feet.

Up the pathway a long procession came very slowly. The Queen headed it; she was royally attired in purple. By her side trotted Georgie Grub, the most fashionable young spark in Garden-land. Behind came Caroline Caterpillar, with Cornelius Caterpillar, her cousin. Then came Florrie Fly, with our old friend Billie Bluebottle, who had left the service of Sammy Starling. Behind all these, in a state carriage, came a little silver elephant.

There, before Silverboy’s astonished gaze, he was reclining on the pansy-leaf cushions of his own private carriage, surrounded with footmen and servants.

“I say”, cried Silverboy to a microbe. “Who’s that?" pointing to the silver elephant.

“Oh! He’s a great man, that,” squeaked the microbe. “He’s going to marry Cissy Centipede next week.”

“Cissy Centipede!” exclaimed Silverboy. “Whoever is Cissy Centipede?”